In my many years of performing music I have met numerous guitarists

(some very accomplished) with varying degrees of trouble tuning their instruments.

I know the reasons why. So let's get started...

Sometimes the problem is that the string is slipping on the tuning peg or is stretching and needs to be replaced. Rarely but possible, the bottom end could be cutting its way through the bridge. These issues are addressed in my "Restringing Neatly" page here.

The real culprit is the friction of the strings in the grooves of the nut. When a tuning peg is tightened the part of the string that is above the nut receives greater tension than the rest until the imbalance is enough to overcome the friction -- and the pitch of the string goes up. The same thing happens when the peg is loosened. The imbalance remains -- just below the threshold of force needed to overcome the friction -- if not corrected. When played in this state the vibration of the string will reduce the friction, and the tension will equalize. The result is that the string will go out of tune. This may seem obvious to some, but not everyone. What to do about it?

First, as mentioned in my "Restringing Neatly" page, lubrication definitely helps. I use a cheap disposable mechanical pencil to 'color-in' the groove. Graphite is definitely the best choice because it is dry. I apply it every time I change my strings -- but it doesn't entirely solve the problem.

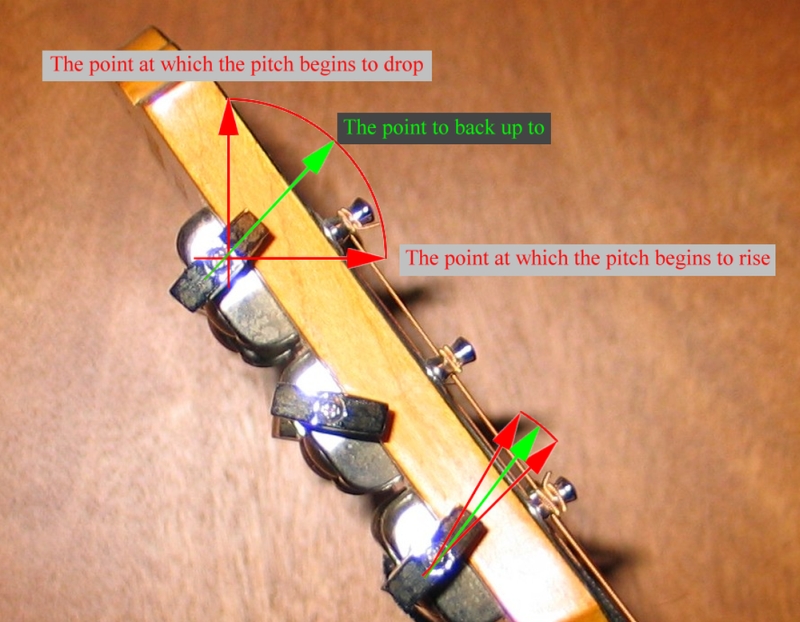

The solution is to equalize the tension when the correct pitch

has been attained. This simply means backing the peg off a little bit. The

trick is to back it off just the right amount. A tuning peg has a range of

motion between pitch up and pitch down caused by the aforementioned friction.

It is the center of this range that the peg needs to be backed off to. It

is easier said than done because the range will be different for each string.

The longer the string is between the nut and peg the more it will stretch,

but also the thinner it is the more it will stretch. On a guitar with a standard

head configuration, the low E string will need very little if any correction

and the G will need the most. To find the range, slowly tighten until the

pitch rises then loosen until the pitch falls. Now tune the string up (or

down) to pitch then back off half the determined range.

As the image above shows, the range of motion of the low E string is much smaller than that of the D. (The ranges shown are slightly exagerated).

There are two other causes for excessive friction at the nut

that I can think of. If the strings are too thick to fit properly into the

grooves -- this can make it very difficult to tune and can lead to broken

strings -- and troughs worn into the grooves of the wound strings -- usually

caused by a lot of playing and no tuning. In either case an audible tink can

be heard as each winding snaps past the restriction. The problem can be fixed

with a little very careful filing or standing of the grooves, but don't overdo

it.

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|